Drugmakers Takeda Pharmaceutical Co. and Roche Holding AG could each be forced to repay the government $100 million annually for wasted medicines under the Senate infrastructure deal.

The $550 billion measure, which the Senate is debating this week, would require companies to refund Medicare when doctors throw away drugs, a move meant to push some drugmakers to stop overpacking single-use containers. The funds would offset part of the bill’s spending on roads and bridges.

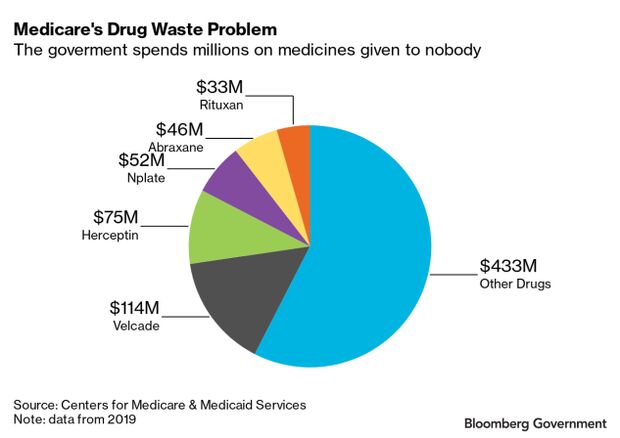

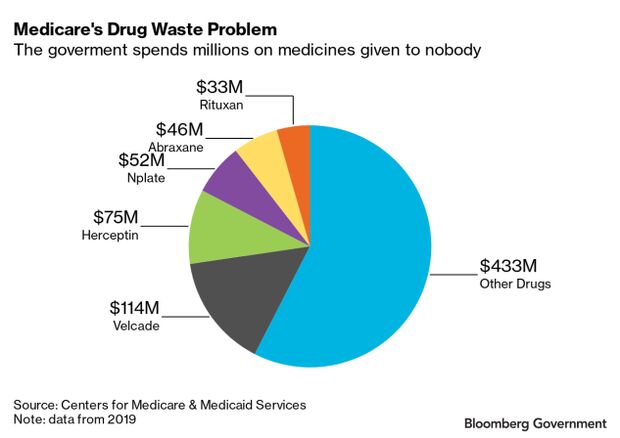

Medicare paid $752.9 million for drugs that were discarded in 2019, according to government data. More than a third, or $286 million, of that spending came from just four drugs, and one — Takeda’s Velcade — accounted for more than $114 million of that spending alone.

Researchers and health-care industry executives say drug waste is a major hidden cost for U.S. insurers, including Medicare, that contributes to rising insurance premiums. The waste also obscures what’s actually being spent on some of the most expensive medicines, in some cases raising the cost of pricey cancer drugs by 20% or more.

“When we talk about the cost of a drug, we’re often not talking about this waste,” said Peter Bach, chief medical officer for Delfi Diagnostics Inc. and a researcher with Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. “This is a lot of money the drug industry has been capturing for years.”

The infrastructure package would require drugmakers to refund Medicare for discarded physician-administered drugs starting in 2023. Drugs that have been covered by Medicare for fewer than 18 months would be exempt, as would some drugs that require a special filtration process.

The top five most-discarded drugs by cost in 2019 were Takeda’s Velcade, Roche’s Herceptin, Amgen Inc.‘s Nplate, Bristol-Myers Squibb Co.‘s Abraxane, and Roche’s Rituxan. Velcade topped the list for all three years Medicare has collected this data, most recently in 2019. Most of these are cancer drugs.

Nicolette Baker, a senior manager for corporate relations at Genentech, part of Roche, said the company’s medicines are packaged according to Food and Drug Administration requirements, which call on companies to ensure that waste is reduced but that a vial typically contains enough for a single dose.

Hospitals and Doctors Win, Pharma Loses in Infrastructure Deal

Why It’s Wasted

Some drug waste is typical for medicines that come in single-use containers where the dose is based on the patient’s weight, said Chris Marcum, vice president of enterprise pharmacy at Cancer Treatment Centers of America Inc., a network of cancer care and research centers. Physicians can either use whatever is left in the container for another patient—or discard it and bill it as waste, he said.

Often these medicines don’t contain preservatives, giving them a shelf life of a few hours, he said.

Velcade, for example, comes to hospitals in a 3.5-milligram vial but the typical dose is around 2.5 milligrams, said Jimmie Deibert, director of clinical pharmacy programs at Cancer Treatment Centers of America.

More than a quarter of what Medicare paid for this chemotherapy drug in 2019—nearly $426 million—was discarded, according to Medicare data. This waste and drugmakers’ list prices hide the true cost of some of the most expensive medicines on the market, Bach said.

For example, Biogen Inc.‘s recently approved Alzheimer’s medicine, Aduhelm, premiered with a price tag of about $56,000 per year. Bach said that’s based on dosing for a person who weighs about 163 pounds, which is below average for U.S. adults. The true annual cost for Aduhelm could be more than $60,000, he said.

Biogen Alzheimer’s Drug Approval to Get Inspector’s Probe

“They’re actively in the business of signaling a price average that is inaccurate,” Bach said of drugmakers.

Some drugmakers say they’re actively working to reduce waste. Amgen in 2019 introduced a smaller vial for Nplate to compliment the larger vials already available, said Kelley Davenport, a spokeswoman.

‘Right-Sizing’ for Cost

Lawmakers who want drugmakers to repay Medicare for wasted drugs say manufacturers intentionally over-package containers to reap more revenue from the government. Without a profit motive, these companies are likely to find ways to reduce waste, said Stacie Dusetzina, a professor of health policy at Vanderbilt University Medical Center.

“If the industry knows that every bit of waste comes out their bottom line, you can imagine they’d do a better job of right-sizing the vial,” she said.

Dusetzina noted that nothing would stop these companies from raising the cost of their drugs to offset what they must refund the government, putting into question whether Medicare would save any money with the refunds over time.

A Senate aide familiar with the provision said the Congressional Budget Office estimated it would save the government $3 billion over 10 years.

In addition to funding part of the infrastructure bill, Bach pointed out that taxpayers would no longer have to foot the bill for overpacked containers. “We’ll get our money back,” he said.

Pharma Could Face Billions in Waste Fines

August 5, 2021 9:20 pm

Drugmakers Takeda Pharmaceutical Co. and Roche Holding AG could each be forced to repay the government $100 million annually for wasted medicines under the Senate infrastructure deal.

The $550 billion measure, which the Senate is debating this week, would require companies to refund Medicare when doctors throw away drugs, a move meant to push some drugmakers to stop overpacking single-use containers. The funds would offset part of the bill’s spending on roads and bridges.

Medicare paid $752.9 million for drugs that were discarded in 2019, according to government data. More than a third, or $286 million, of that spending came from just four drugs, and one — Takeda’s Velcade — accounted for more than $114 million of that spending alone.

Researchers and health-care industry executives say drug waste is a major hidden cost for U.S. insurers, including Medicare, that contributes to rising insurance premiums. The waste also obscures what’s actually being spent on some of the most expensive medicines, in some cases raising the cost of pricey cancer drugs by 20% or more.

“When we talk about the cost of a drug, we’re often not talking about this waste,” said Peter Bach, chief medical officer for Delfi Diagnostics Inc. and a researcher with Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. “This is a lot of money the drug industry has been capturing for years.”

The infrastructure package would require drugmakers to refund Medicare for discarded physician-administered drugs starting in 2023. Drugs that have been covered by Medicare for fewer than 18 months would be exempt, as would some drugs that require a special filtration process.

The top five most-discarded drugs by cost in 2019 were Takeda’s Velcade, Roche’s Herceptin, Amgen Inc.‘s Nplate, Bristol-Myers Squibb Co.‘s Abraxane, and Roche’s Rituxan. Velcade topped the list for all three years Medicare has collected this data, most recently in 2019. Most of these are cancer drugs.

Nicolette Baker, a senior manager for corporate relations at Genentech, part of Roche, said the company’s medicines are packaged according to Food and Drug Administration requirements, which call on companies to ensure that waste is reduced but that a vial typically contains enough for a single dose.

Hospitals and Doctors Win, Pharma Loses in Infrastructure Deal

Why It’s Wasted

Some drug waste is typical for medicines that come in single-use containers where the dose is based on the patient’s weight, said Chris Marcum, vice president of enterprise pharmacy at Cancer Treatment Centers of America Inc., a network of cancer care and research centers. Physicians can either use whatever is left in the container for another patient—or discard it and bill it as waste, he said.

Often these medicines don’t contain preservatives, giving them a shelf life of a few hours, he said.

Velcade, for example, comes to hospitals in a 3.5-milligram vial but the typical dose is around 2.5 milligrams, said Jimmie Deibert, director of clinical pharmacy programs at Cancer Treatment Centers of America.

More than a quarter of what Medicare paid for this chemotherapy drug in 2019—nearly $426 million—was discarded, according to Medicare data. This waste and drugmakers’ list prices hide the true cost of some of the most expensive medicines on the market, Bach said.

For example, Biogen Inc.‘s recently approved Alzheimer’s medicine, Aduhelm, premiered with a price tag of about $56,000 per year. Bach said that’s based on dosing for a person who weighs about 163 pounds, which is below average for U.S. adults. The true annual cost for Aduhelm could be more than $60,000, he said.

Biogen Alzheimer’s Drug Approval to Get Inspector’s Probe

“They’re actively in the business of signaling a price average that is inaccurate,” Bach said of drugmakers.

Some drugmakers say they’re actively working to reduce waste. Amgen in 2019 introduced a smaller vial for Nplate to compliment the larger vials already available, said Kelley Davenport, a spokeswoman.

‘Right-Sizing’ for Cost

Lawmakers who want drugmakers to repay Medicare for wasted drugs say manufacturers intentionally over-package containers to reap more revenue from the government. Without a profit motive, these companies are likely to find ways to reduce waste, said Stacie Dusetzina, a professor of health policy at Vanderbilt University Medical Center.

“If the industry knows that every bit of waste comes out their bottom line, you can imagine they’d do a better job of right-sizing the vial,” she said.

Dusetzina noted that nothing would stop these companies from raising the cost of their drugs to offset what they must refund the government, putting into question whether Medicare would save any money with the refunds over time.

A Senate aide familiar with the provision said the Congressional Budget Office estimated it would save the government $3 billion over 10 years.

In addition to funding part of the infrastructure bill, Bach pointed out that taxpayers would no longer have to foot the bill for overpacked containers. “We’ll get our money back,” he said.